A good understanding on memory layout is essential for every programmer, especially C/C++ programmer. Unlike other languages, C++ gives the programmer a total control over memory management. Some might see this as an advantage, and some might not, as more control indicates more responsibility and efforts to a programmer. Or, put differently, you can manage your program’s memory efficiently if you know what you are doing.

It’s a programmer responsibility to understand memory and manage it well.

Overview

This article covers the basic of program’s memory layout on x86-64 architecture, including how CPU allocates memory when a C/C++ program is executed, and where are those variables stored.

Here are the subtopics covered :

The amount of memory allocated for a running program and how it is allocated are architecture-dependent and OS-dependent. For instance, the amount of memory allocated to the program running on an Android phone and a game console PS4 is different. Thus, it is important to mention which OS and architecture we are using here.

The explanation in this article is based on a 64-bit CPU running macOS (based on Unix Operating System). Furthermore, lldb is used for the demonstration.

Memory Representation

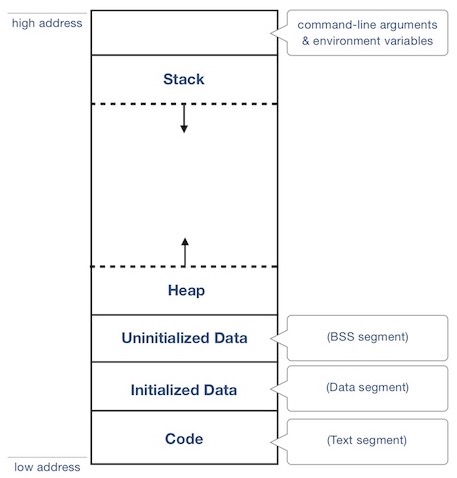

A typical memory representation of a C++ program can be divided into 5 sections. In fact, there are more than just these 5 sections, but these are the sections we are interested in for the moment.

-

Code Segment (Text Segment)

Contains machine instructions from compiled program, which represented in binary form. Obviously, we can always disassemble these instructions using debugging tool to convert it into human-readable assemly language.Code segment is usually read-only, since we don’t want to accidentally modify the instructions.

-

Initialized Data Segment (Data Segment)

Contains initialized global variables and static variables.Can be further categorized into 2 parts :

-

Initialized read-only area

e.g.const float PI = 3.142; -

Initialized read-write area

e.g.int num = 50;

-

-

Uninitialized Data Segment (BSS Segment)

Contains global and static variables that are not explicitly initialized in the source code. -

Stack

Contains local function variables and other function related data. Refer to stack segment for more detailed information. -

Heap

Contains dynamic allocated data (data allocated at runtime).

(More detailed information will be covered in another article(wip.)

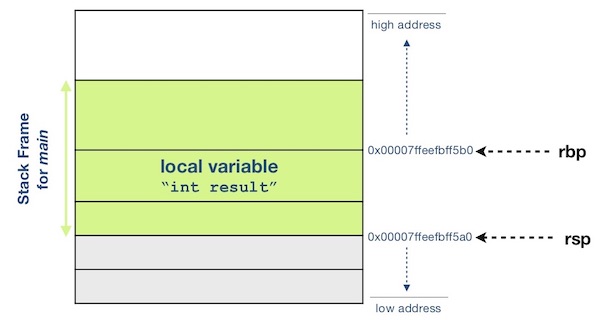

The figure below shows an overview of program’s memory layout. Noticed that the stack segment grows downwards. Of course, there is a reason behind this design, and the growing direction is architecture-dependent too. However, those are not the concern in this article, just keep in mind that everything pushed onto the stack segment results in a lower address in most architectures. Thus, the “top of the stack” actually located at lower address in the memory.

Stack Segment

Stack segment is a block of memory used as a temporary storage to store the program stack (a.k.a call stack) of an executed program. Program stack is just a collection of stack frames holding function related data including function parameters, return address, and local variables.

For instance, the program stack of an application with main function calling funcA, and funcA calling funcB can be view as the picture below :

Registers

It is good to know what is a register first in order to fully understand program stack. Registers are small and quickly accessible memory available on CPU, and they are used for data & instruction processing. The number, size, and type of registers are vary according to processor.

Here, I’ll only cover some special purpose registers that are frequently used for stack frame. If you are interested, there are plenty of resources available, such as microsoft docs’s x64 architecture.

Below is some registers used to keep track of call stack and program instructions. Each register has different name based on different architecture. For instance,

Base Pointer Register (BP)

This register stores the base address of the stack frame.

- BP (16-bit architecture)

- EBP (32-bit architecture)

- RBP (64-bit architecture)

Stack Pointer Register (SP)

This register stores the address of the top of stack frame.

- SP (16-bit architecture)

- ESP (32-bit architecture)

- RSP (64-bit architecture)

Instruction pointer register (IP)

This register stores machine instruction to be executed next.

- IP (16-bit architecture)

- EIP (32-bit architecture)

- RIP (64-bit architecture)

Function Call Mechanism

It’s easier to understand program stack by studying how a function is called and how function parameters are stored in the memory. In addition, it is beneficial to have basic knowledge in assembly, as you can easily understand what happen in program stack and registers by running through each line of code. Therefore, a simple disassembled C++ program is used to demonstrate function call mechanism.

Here is the code used for demonstration:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int calculate() {

int a = 3;

int b = 4;

return add(a, b);

}

int main() {

int result = calculate(); // <-- breakpoint

return 0;

}

As you can see, there are 2 functions invoked in this program. First, main calls function calculate, followed by calculate calls function add.

Now, let’s set a breakpoint on line 12 and go through the program step by step.

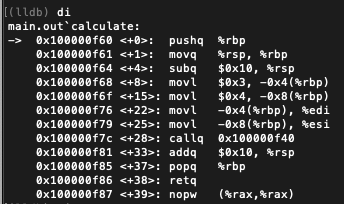

If we look at the assembly code now, we will notice that the rip is pointing to instruction "callq 0x100000f60", which is the instruction to be executed.

Part I : Calling function calculate

-

"callq 0x100000f60"

An execution of call instruction means an update onripvalue , causing it pointing to the called function’s instruction. In this case, the oldripvalue (a.k.a return address) will dissapear if CPU doesn’t store it somewhere before the update. Monitoring return address is necessary so that CPU knows which instruction to execute next after the called function finished executing.Thus,

"callq"instruction performs two steps :-

Push return address onto the stack.

According to the assembly code shown, the return address is0x100000fa4. -

Update

ripto point to the new address provided.

Now,ripis pointing to0x100000f60, which is the first instruction in functioncalculate.

-

-

"pushq %rbp"

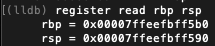

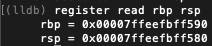

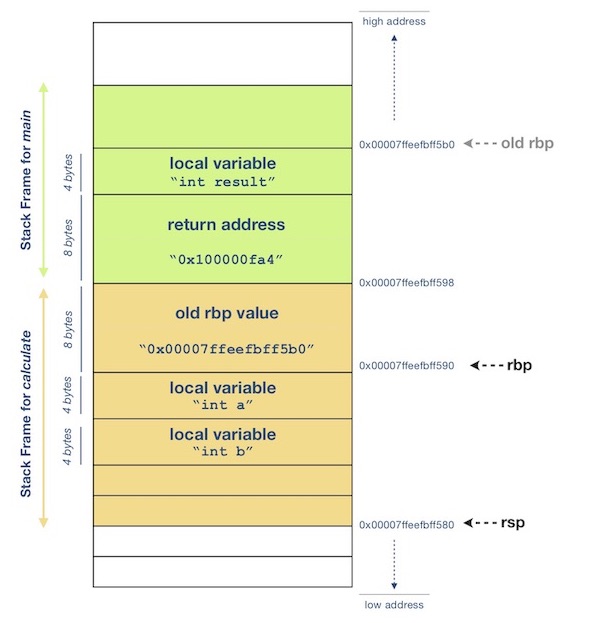

The next instruction “push”rbpvalue onto stack (currentrbpvalue is0x00007ffeefbff5b0, pointing to main stack frame). In the meantime,rspis updated to points to the top of the stack (0x00007ffeefbff590).We can varify the values in registers as below:

-

"movq %rsp, %rbp"

Then,"movq"instruction copyrspvalue torbp. At this stage,rspis pointing to the top of stack, which is also the base address of new stack frame (calculate stack frame).After the execution,

rbpis pointing to the same address asrsp. -

"subq $0x10, %rsp"

Next, a 16 bytes reserved space is allocated for function local variables by substracting10Htorsp. Now,rspis pointing to0x00007ffeefbff580.

"movl $0x3, -0x4(%rbp)"-

"movl $0x4, -0x8(%rbp)"

Functioncalculatedeclares two local variables and initializes them to 3 and 4 accordingly. In assembly, this is performed by :- move value 3 to address -0x4(%rbp)

- equivalent to 0x00007ffeefbff590 - 0x4 = 0x00007ffeefbff58c

- move value 4 to address -0x8(%rbp)

Noted that 4 bytes has been allocated for each local variable, as variableaandbare both integer.

- move value 3 to address -0x4(%rbp)

- latest overview of program stack

Now, the overall program stack will look like this :

Part II : Calling function add

Now, function calculate calls function add at line 8, passing in two arguments a and b, then return the result.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int calculate() {

int a = 3;

int b = 4;

return add(a, b); // <--- calling function add.

}

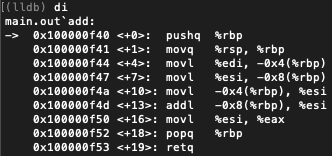

Here is the assembly code for function add :

If the called function receives parameters, the parameters will either be push onto the stack or save into registers, depends on the OS.

As mentioned, I’m using macOS to run the program, and it is based on the Unix operating system, which follows the calling convention of System V AMD64 ABI. According to the ABI, the first 6 arguments passed to a function are saved into registers, and the 7th and onwards arguments are pushed onto stack.

The table below shows where each argument is save :

| n-th argument | : | location |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | : | rdi |

| 2nd | : | rsi |

| 3rd | : | rdx |

| 4th | : | rcx |

| 5th | : | r8 |

| 6th | : | r9 |

| 7th onwards | : | stack |

Thus, the overall process for function calculate to call function add can be break down to :

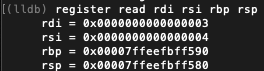

- Push parameters into registers.

Since this program is run on macOS, the 2 arguments are saved into registersrdiandrsi. Thus, no parameters are pushed onto the stack. Noticed thatrdiis holding value 3, andrsiholding value 4 as shown in below :

- Push “return address” onto stack.

- Push

rbpvalue onto stack.

Currently,rspis pointing to the top of stack, which is the new stack frame address for functionadd. - Copy

rspvalue torbp.

Now,rbpis pointing to the new stack frame address. - Execute the body of function

add.

Here, the 2 values are moved to temporary storage called “red zone”, added, and the result is saved ineaxregister.

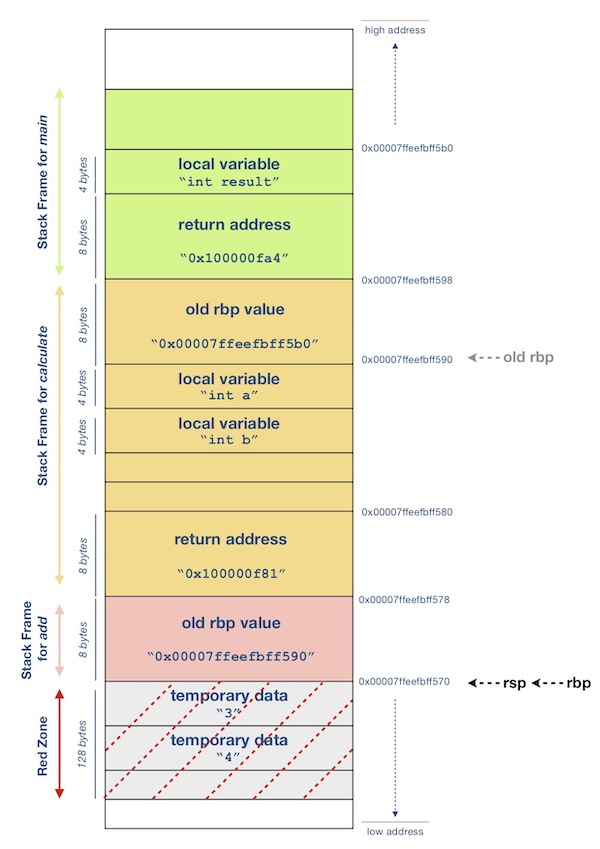

Now, the overall program stack will looks like this :

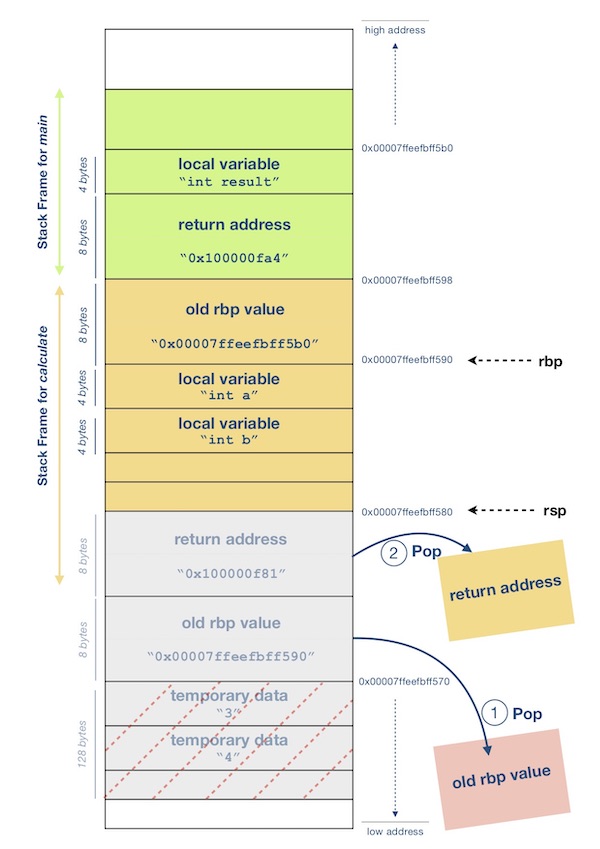

Next, as the function exits, it will :

-

Pops the old

rbpvalue from the top of stack, and updaterbp.

After the execution,rbpis now pointing back to the base address of “calculate stack frame”. -

Pops the “return address” from stack, and update the

ripvalue.

By updating theripvalue, the instruction pointer register is now pointing to the next instruction to be executed incalculatefunction. Thus, returning the control to the calling function.

Let’s have a look on the latest program stack. Noticed that rbp is now pointing back to “calculate stack frame”, and rsp to the top of “calculate stack frame”.

Part III : Exiting function calculate

Since function calculate has 16 bytes reserved space allocated for it’s local variables. Before the function exit, rsp is set back to the stack frame’s base address.

Below are the steps :

-

Rspis set back to whererbpis pointing. This is done by adding 16 bytes back torsp. -

Next steps are similar for all exiting function. The old

rbpvalue is poped from stack, followed by “return address”.

Now the control is returning to main function, noticed that rbp is pointing to the base of main stack frame and rsp to the top of stack as below.